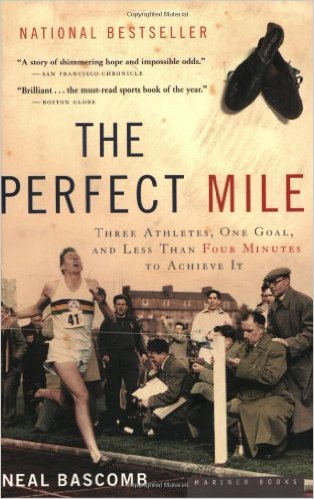

The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve It

There was a time when running the mile in four minutes was believed to be beyond the limits of human foot speed, and in all of sport it was the elusive holy grail. In 1952, after suffering defeat at the Helsinki Olympics, three world-class runners each set out to break this barrier. Roger Bannister was a young English medical student who epitomized the ideal of the amateur — still driven not just by winning but by the nobility of the pursuit. John Landy was the privileged son of a genteel Australian family, who as a boy preferred butterfly collecting to running but who trained relentlessly in an almost spiritual attempt to shape his body to this singular task. Then there was Wes Santee, the swaggering American, a Kansas farm boy and natural athlete who believed he was just plain better than everybody else.

Spanning three continents and defying the odds, their collective quest captivated the world and stole headlines from the Korean War, the atomic race, and such legendary figures as Edmund Hillary, Willie Mays, Native Dancer, and Ben Hogan. In the tradition of Seabiscuit and Chariots of Fire, Neal Bascomb delivers a breathtaking story of unlikely heroes and leaves us with a lasting portrait of the twilight years of the golden age of sport.

From Publishers Weekly

The attempt by three men in the 1950s to become the first to run the mile in less than four minutes is a classic 20th-century sports story. Bascomb's excellent account captures all of the human drama and competitive excitement of this legendary racing event. It helps that the story and its characters are so engaging to begin with. The three rivals span the globe: England's Roger Bannister, who combines the rigors of athletic training with the "grueling life of a medical student"; Australia's John Landy, "driven by a demand to push himself to the limit"; and Wes Santee from the U.S., a brilliant strategic runner who became the "victim" of the "[h]ypocrisy and unchecked power" of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). Although Bannister broke the record before Landy, Landy soon broke Bannister's record, and the climax of the book is a long and superb account of the race between the two men at the Empire Games in Vancouver on August 7, 1954. Bascomb provides the essential details of this "Dream Race"â€"which was heard over the radio by 100 million peopleâ€"while Santee, who may have been able to beat both of them, was forced by AAU restrictions to participate only as a broadcast announcer. Bascomb definitively shows how this perfect race not only was a "defining moment in the history of the mileâ€"and of sport as well," but also how it reveals "a sporting world in transition" from amateurism to professionalism.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From The New Yorker

On May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister, a British medical student who squeezed in track workouts between hospital rounds, became the first man to run a mile in less than four minutes. It was a feat that had widely been thought impossible, but within seven weeks an even faster time was posted by the Australian John Landy, setting up a showdown later that year in a race that was billed as the "Mile of the Century." In masterly fashion, Bascomb re-creates the battle of the milers, embellishing his account with fascinating forays into runner's lore. (In the seventeenth century, athletes had their spleens excised to boost speed; in the nineteenth, they were advised to rest in bed at noon naked.) It's a mark of Bascomb's skill that, although the outcome of the race is well known, he keeps us in suspense, rendering in graphic detail the runners' agony down the final stretch.

Copyright © 2005 The New Yorker

The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve It Review

'Bascomb succeeds in seducing the reader into sympathising with them all and feeling involved in their individual stories' The Spectator 'The Perfect Mile is as inspiring as it is accurate and evocative' Athletics Weekly magazine 'Bascomb lets his wonderful story and its characters do the talking' Sunday Telegraph --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

About The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve It Author

How did he know he would not die?” a Frenchman asked of the first runner to break the four-minute mile. Half a century ago the ambition to achieve that goal equaled scaling Everest or sailing alone around the world. Most people considered running four laps of the track in four minutes to be beyond the limits of human speed. It was foolhardy and possibly dangerous to attempt. Some thought that rather than a lifetime of glory, honor, and fortune, a hearse would be waiting for the first person to accomplish the feat.

The four-minute mile: this was the barrier, both physical and psychological, that begged to be broken. The number had a certain mathematical elegance. As one writer explained, the figure “seemed so perfectly round—four laps, four quarter miles, four-point-oh-oh minutes —that it seemed God himself had established it as man’s limit.” Under four minutes—the place had the mysterious and heroic resonance of reaching sport’s Valhalla. For decades the best middle-distance runners had tried and failed. They had come to within two seconds, but that was as close as they were able to get. Attempt after spirited attempt had proved futile. Each effort was like a stone added to a wall that looked increasingly impossible to breach.

But the four-minute mile had a fascination beyond its mathematical roundness and assumed impossibility. Running the mile was an art form in itself. The distance—unlike the 100-yard sprint or the marathon —required a balance of speed and stamina. The person to break that barrier would have to be fast, diligently trained, and supremely aware of his body so that he would cross the finish line just at the point of complete exhaustion. Further, the four-minute mile had to be won alone. There could be no teammates to blame, no coach during halftime to inspire a comeback. One might hide behind the excuses of cold weather, an unkind wind, a slow track, or jostling competition, but ultimately these obstacles had to be defied. Winning a footrace, particularly one waged against the clock, was ultimately a battle with oneself, over oneself.

In August 1952 the battle commenced. Three young men in their early twenties set out to be the first to break the barrier. Born to run fast, Wes Santee, the “Dizzy Dean of the Cinders,” was a natural athlete and the son of a Kansas ranch hand. He amazed crowds with his running feats, basked in the publicity, and was the first to announce his intention of running the mile in four minutes. “He just flat believed he was better than anybody else,” said one sportswriter. Few knew that running was his escape from a brutal childhood.

Then there was John Landy, the Australian who trained harder than anyone else and had the weight of a nation’s expectations on his shoulders. The mile for Landy was more aesthetic achievement than footrace. He said, “I’d rather lose a 3:58 mile than win one in 4:10.” Landy ran night and day, across fields, through woods, up sand dunes, along the beach in knee-deep surf. Running revealed to him a discipline he never knew he had.

And finally there was Roger Bannister, the English medical student who epitomized the ideal of the amateur athlete in a world being overrun by professionals and the commercialization of sport. For Bannister the four-minute mile was “a challenge of the human spirit,” but one to be realized with a calculated plan. It required scientific experiments, the wisdom of a man who knew great suffering, and a magnificent finishing kick.

All three runners endured thousands of hours of training to shape their bodies and minds. They ran more miles in a year than many of us walk in a lifetime. They spent a large part of their youth struggling for breath. They trained week after week to the point of collapse, all to shave off a second, maybe two, during a mile race—the time it takes to snap one’s fingers and register the sound. There were sleepless nights and training sessions in rain, sleet, snow, and scorching heat. There were times when they wanted to go out for a beer or a date yet knew they couldn’t. They understood that life was somehow different for them, that idle happiness eluded them. If they weren’t training or racing or gathering the will required for these efforts, they were trying not to think about training and racing at all.

In 1953 and 1954, as Santee, Landy, and Bannister attacked the four-minute barrier, getting closer with every passing month, their stories were splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world, alongside headlines about the Korean War, Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, and Edmund Hillary’s climb toward the world’s rooftop. Their performances outdrew baseball pennant races, cricket test matches, horse derbies,, rugby matches, football games, and golf majors. Ben Hogan, Rocky Marciano, Willie Mays, Bill Tilden, and Native Dancer were often iiiiin the shadows of the three runners, whose achievements attracted media attention to track and field that has never been equaled since. For weeks in advance of every race the headlines heralded an impending break in the barrier: “Landy Likely to Achieve Impossible!”; “Bannister Gets Chance of 4-Minute Mile!”; “Santee Admits Getting Closer to Phantom Mile.” Articles dissected track conditions and the latest weather forecasts. Millions around the world followed every attempt. When each runner failed—and there were many failures—he was criticized for coming up short, for not having what it took. Each such episode only motivated the others to try harder.

They fought on, reluctant heroes whose ambition was fueled by a desire to achieve the goal and to be the best. They had fame, undeniably, but of the three men only Santee enjoyed the publicity, and that proved to be more of a burden than an advantage. As for riches, financial reward was hardly a factor—they were all amateurs. They had to scrape around for pocket change, relying on their hosts at races for decent room and board. The prize for winning a meet was usually a watch or a small trophy. At that time, the dawn of television, amateur sport was beginning to lose its innocence to the new spirit of “win at any cost,” but these three strove only for the sake of the attempt. The reward was in the effort.

After four soul-crushing laps around the track, one of the three finally breasted the tape in 3:59.4, but the race did not end there. The barrier was broken, and a media maelstrom descended on the victor, yet the ultimate question remained: who would be the best when they toed the starting line together?

The answer came in the perfect mile, a race fought not against the clock but against one another. It was won with a terrific burst around the final bend in front of an audience spanning the globe.

If sport, as a chronicler of this battle once said, is a “tapestry of alternating triumph and tragedy,” then the first thread of this story begins with tragedy. It occurred in a race 120 yards short of a mile at the 1,500- meter Olympic final in Helsinki, Finland, almost two years to the day before the greatest of triumphs.

Copyright © 2004 by Neal Bascomb. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

--This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

Based on ample first-hand details gleaned from interviewing Roger Bannister, John Landy and Wes Santee, "The Perfect Mile" provides a nuanced character study of what drives these three great men toward breaking the most elusive of athletic goals: the four-minute-mile. While serious students of the sport will know the outcome of this tale before reading it, Neal Bascomb is able to create and maintain a fair amount of suspense by allowing the reader to experience events leading up to the 1954 Empire Games showdown from three very different perspectives.

Roger Bannister is the thinking man's runner, with the classic middle distance athlete's long stride and finishing kick as well as insights into the scientific principles that underlie cardiovascular exertion. These strengths, however, are offset by the demanding medical studies that severely limit his training time and by his tendency to become overwrought before big races.

John Landy is the workhorse of the trio, logging more miles than the others and able to bring a single-minded focus to the task. But he lacks the closing speed and power of the classic milers, forcing him to run the legs out of his competitors from the front.

Wes Santee, the least famous and accomplished of the three, may well be the most talented. Yet the demands of his University of Kansas track schedule, military commitments, and confrontations with track and field's governing body are impediments that prove too difficult to overcome.

For me, the best part of this book was the fact that these three men pursued this historic goal in a noble and dignified fashion that made you really pull for each of them somehow to be the first.

I found the climax of this story-Bannister and Landy's race in Vancouver in 1955-to be almost impossibly gripping. This whole book is just about perfect. It is about a particular athletic quest, and it is also about a key transition period in sport.

There were two related aspects to change at this time in track and field (and by extension other already professional sports). The more obvious was the glaring contradiction between the old, 100% pure amateur model on the one hand, and the growing business and media phenomenon we know today on the other. This subtext is brought out in the second part of the story, and especially in the sad tale of the straight-talking American, Wes Santee.

But this was also a period of radical change in training methods. Emil Zatopek, the Czech runner who won the 5,000 meter, 10,000 meter, AND marathon runs at the 1952 Olympics, is the key figure at the outset of the book. His successes taught runners like Bannister, Landy, and Santee that more training, and harder training, would yield faster times. The author outlines older ideas of conditioning that look ridiculously precious and half-hearted by modern standards. As a masters athlete I was especially struck by this phase of the story, and the author does a good job of recapping the sorts of training the runners did throughout.

The three are so characteristic of their countries, they could almost be fictional types. American Wes Santee is brash and outspoken. It is he who calls the financial bluff of the Neanderthal-like powers that ruled amateur athletics in his day, and it is he who is most severely victimized in the process. (In a kind of entrapment scenario, he was given extra money by one set of AAU officials, and then banned for life by others.